Your cart is currently empty!

Desertification Happens When Raindrops Meet Him at the Bar Instead of Percolating into Groundwater: Stay Thirsty, My Friends

Issue 1 / Chapter 1

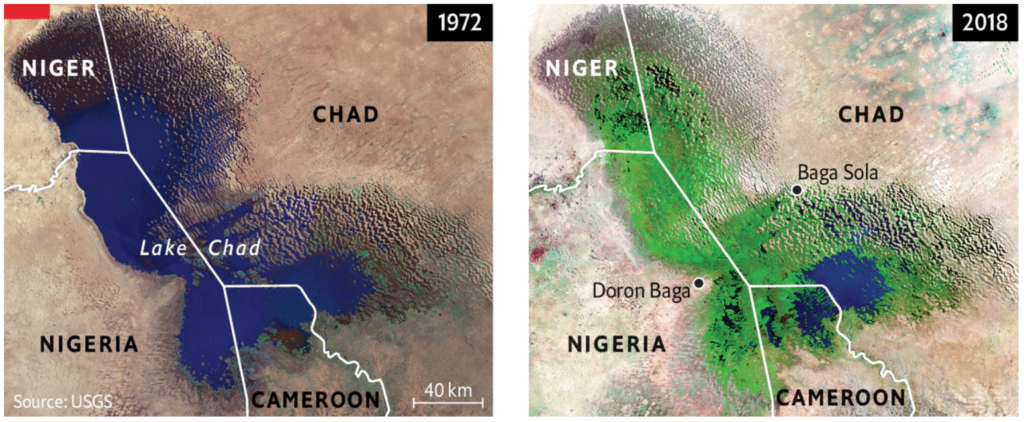

Issue 1 of Finite examines the effects of climate change on freshwater ecosystems and humanity’s access to drinking water, using Cameroon and Lake Chad as a case study to understand (unfortunately) common problems. Specifically, we are trying to get to the bottom of two mysteries. First, why has Lake Chad lost 90% of its volume? And second, why do half of the people of Cameroon – one of the countries bordering Lake Chad and home to 28 million people – lack access to clean drinking water?

For our first mystery – the collapse of Lake Chad – the basic problem is improper management of natural resources. However, as alluded to in the introduction to Issue 1, the fundamental reason behind improper resource management is hunger and poverty, an issue we will look at in detail in Chapter 3. For now, in Chapter 1, we’re limiting ourselves to the scientific and technological aspects of these problems.

____________________________________

Issue 1: Climate Change and Freshwater

Intro: Why did Lake Chad collapse and why are Cameroonians so thirsty?

Chapter 1: Desertification of the Sahel and Cameroon’s water infrastructure

Chapter 2: Cameroon gains “independence” from France

Chapter 3: Poverty, structural adjustments, and dictators

Chapter 4: The US New Deal’s Soil Conservation Service is a proven model

Bonus 1: More on Cameroon’s independence movement

Bonus 2: How did Ahidjo make himself a dictator?

Bonus 3: How did Biya take control from Ahidjo?

_____

Issue 1 is available in written and podcast format

__________

How (but not why) to kill a lake

As mentioned in the Issue 1 introduction, in 60 years, Lake Chad’s volume has plummeted by 90% and its surface area has dropped from 26,000 square kilometers in 1963 to less than 1,500 square kilometers. In the 1960s, before it started losing volume, Lake Chad had approximately the surface area of Lake Erie. Now, it is similar in size to the Great Salt Lake. It went from about the size of Maryland to about the size of Los Angeles. It’s an ecological catastrophe.

What happened?

The science is very clear. First, Lake Chad is fed by three rivers, and ten cubic kilometers are diverted away from Lake Chad each year for irresponsible irrigation projects. Ten cubic kilometers is so much water that you could cover the entire US state of Delaware with a meter of water – water up to your hips across the entire state – and still have enough water left to do the same to Rhode Island. Ten cubic kilometers is an unfathomably large amount of water, and that is the amount diverted away from Lake Chad each year. The other major contributor to the Lake Chad catastrophe is the desertification of the Sahel, the region of Africa where Lake Chad and Cameroon are located. Though scientists continue to debate the exact breakdown, there is no question that these two causes are together responsible for the collapse of Lake Chad.

Let’s investigate these two causes in much greater detail.

Diversions

The Ngadda River feeds Lake Chad from the southwest, the Yobe River from the west, and the Chari and Logone Rivers from the southeast. The Ngadda River only flows seasonally and contributes an insignificant amount to Lake Chad. The Yobe River contributes about 10% of the water flowing into Lake Chad; the vast majority, 90%, comes from the Chari and Logone river system. The Chari is the larger of the two rivers, and the Logone is technically a tributary of the Chari since the Logone – though very large – is slightly smaller and joins the Chari before entering Lake Chad.

90% of the water entering Lake Chad comes from the southeast due to the unique climate of the Lake Chad basin. Most of the Lake Chad basin – approximately two-thirds – has an arid climate: little rain falls, so rivers are small or seasonal. By contrast, the southeastern third of the Lake Chad basin has a monsoon climate: large, seasonal rains fall in June, July, and August. The water from these monsoons drains into one of the dozens of tributaries of the Chari and Logone Rivers, which eventually connect to the Chari and Logone Rivers and then into Lake Chad. This journey takes about six months, so Lake Chad generally reaches its peak volume in December or January, six months after the monsoons.

In sum, 90% of the water entering Lake Chad comes from the monsoons that fall far away to the southeast. The waters from the monsoons are carried north by the Chari-Logone river system, finally draining into Lake Chad.

Any drop of water diverted for irrigation from the Chari-Logone river system is a drop of water prevented from reaching Lake Chad. Environmental scientists have estimated that into the 1960s, diversions for agriculture were negligible, but by the end of the 1970s, had grown to roughly two cubic kilometers per year. In the early 1980s, diversions increased rapidly, and by the 2000s, had reached a whopping ten cubic kilometers per year – out of 40 cubic kilometers total that are estimated to flow into Lake Chad each year. In other words, for every four drops of water that would enter Lake Chad naturally, one is taken away by humans for agricultural purposes.

So that explains one reason why Lake Chad collapsed: 90% of the 40 cubic kilometers of water entering Lake Chad annually comes from the Chari-Logone river system, but approximately ten cubic kilometers of water is diverted out of Chari-Logone each year for agricultural uses.

But this simple answer leads us to more questions. If diversions started in the 1970s, why did Lake Chad begin losing volume in the 1960s? And why did people suddenly start diverting so much water in the 1980s?

Desertification

The second factor contributing to Lake Chad’s collapse – desertification of the Sahel – can answer these questions.

Desertification has been a serious problem for decades in Cameroon, Lake Chad, and the entire Sahel. Desertification is often misunderstood as the encroachment of a desert on fertile lands. This is incorrect; desertification can occur anywhere that land degrades to the point where it can no longer support vegetation: basically, the soil becomes so compacted that plant roots can’t work their way into the soil, nor can any rain. Thus, any rain that falls immediately washes away; though it may rain heavily, the land is generally dry, resembling a desert. The Sahel is near the Sahara Desert, but that’s merely coincidence: desertification isn’t happening because of the Sahara, but because of irresponsible land use. Desertification is a confusing term because it seems to imply that the Sahara is expanding southward, but it’s not; “land degradation” might be a less confusing way to think about it.

In any case, the science of desertification has been understood for many decades. Few have understood the science better than Harold Dregne, who began his career fighting the Dust Bowl as a member of the United States Soil Conservation Service, a vital but often-forgotten part of the New Deal in the 1930s. He eventually wound up as a professor of plant and soil science at Texas Tech University. In a peer-reviewed article from 1986(!) Dregne wrote, “Research has been undertaken in many countries to develop techniques of grazing management and soil and water conservation that would halt and reverse desertification. As a result, there is now a good understanding of the basic principles of land conservation.” And, “Solutions to desertification problems in Africa are known – and in general – can be implemented readily if resources are available to do so.”

As a dramatic illustration, Dregne points to an aerial photograph taken during a 1970s drought of a fenced-in ranch in Niger that had been responsibly managed. The ranch is lush and green, but the land outside the fence is brown and dead. It looks as though a rectangle of healthy savannah were dropped in the middle of a desert – it’s almost a night and day difference.

Inside the fence, land had been responsibly managed. Though receiving the same amount of rain, the land outside the fence had been badly mismanaged, resulting in desertification. Dregne explains:

A [common] misconception is that droughts are responsible for desertification. Droughts do increase the likelihood that the rate of degradation will increase on non-irrigated land if the carrying capacity is exceeded. However, well-managed land will recover from droughts with minimal adverse effects when the rains return. The deadly combination is land abuse during good periods and its continuation during periods of deficient rainfall.

A photograph (via Russ Schnell of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), also taken in Niger, shows land recovering from drought in 1974:

Remarkably, this land suffered not only a severe drought but also severe overgrazing. But because the land wasn’t so badly degraded that desertification set in, once the drought ended, vegetation returned, and the land recovered.

By contrast, here is a photo of desertified land nearby, also in Niger:

This photo clearly illustrates that lack of water is not an issue. Larger plants that were able to recover from overgrazing are lush and green, but otherwise, the ground is devoid of vegetation. Clearly, there is adequate water for plant life. The problem is that new plants cannot take root in the compacted soil.

Laurie Schmidt of NASA’s Earth Observatory points out that desertification of the Sahel is basically the exact same phenomenon as the American Dust Bowl of the 1930s, which caused incalculable economic losses and created 2.5 million refugees. The root cause of the Dust Bowl was poor land management practices, an idea we’ll return to later.

For the Sahel, three things are leading to desertification. First, soils are being exhausted by agriculture. This is happening in two different ways. First, farmers are shortening fallow periods between harvesting and planting. Leaving fields fallow allows the soil to regenerate nutrients; when land isn’t left fallow for long enough, the soil can’t regenerate itself, and crop yields decrease with each harvest. Over many years of too-short fallow periods, the soil becomes completely exhausted and unable to support any plant life, whether crops or wild plants. The lack of plant roots to break up the soil leads to compacted soil, starting the desertification process.

The second process leading to soil exhaustion is the use of drier, less suitable land for agriculture. These marginal soils are quickly exhausted even with long fallow periods; exhausting the soil begins the desertification process.

The second factor leading to desertification in the Sahel is overgrazing. Typically, grazing livestock is not a problem for grasslands; the flocks eat and then move on, the plants regrow, and the land recovers. However, when land is overgrazed, livestock return to areas they have recently grazed, eating the plants faster than they can regrow. Moreover, new plants also have difficulty growing or sprouting from seed because the livestock compact the soil with their hooves, packing it down so tightly that roots cannot work their way through the soil. This leads to ever-expanding dead patches where old plants cannot regrow and new plants cannot establish themselves.

The third factor leading to desertification in the Sahel is deforestation. Trees are being chopped down faster than they can renew themselves. In some climates, this would lead to grassland replacing the forests; however, owing to its arid climate, deforestation leads to soil compaction and desertification.

For many decades, soil scientists have understood that alone drought cannot cause desertification. Responsibly managed land recovers quickly after a drought, even a severe one. However, each of the factors creating desertification in the Sahel – exhausted agricultural soils, overgrazing, and deforestation – is accelerated by drought.

What’s more, very heavy rain and even flooding can occur on desertified land. However, rainwater water quickly flows away, unable to soak into the compacted soil.

Since desertification is caused by compacted soils, it can be reversed by breaking up the soils enough to allow new plants to grow. Once plants establish themselves, the land can heal itself.

Dregne, the land degradation expert, concluded that “Solutions to desertification problems in Africa are known – and in general – can be implemented readily if resources are available to do so.” How readily? A recent report from the UN points out that a single tractor can break up the same surface area of compacted soils as two thousand farmers working by hand with shovels. However, the tractor actually does a better job because it is capable of digging deeper than people can working by hand. A fleet of tractors with specialized plows for breaking up compacted soils – plus responsible land management going forward – is all that would take to completely reverse desertification in the entire Sahel.

So – desertification has been happening to the land around Lake Chad, but why would this contribute to Lake Chad’s collapse? After all, if rain is still falling, wouldn’t it wind up in Lake Chad eventually?

The issue is that plants affect the amount of rain that falls through a process known as transpiration. Plants draw water from the ground, but much of it leaves through their leaves as water vapor. One missing plant means that the air is a tiny bit drier due to the fact that the absent plant no longer adds moisture to the air through transpiration. When plants are lost at the levels seen in the Sahel, it dramatically diminishes the moisture level in the air, thus decreasing the amount of clouds and, ultimately, rainfall. In other words, because of desertification, less rain is falling and the entire region is becoming more dry. This accelerates desertification, but it also means less rainwater entering Lake Chad.

So, desertification accelerated in the mid-1900s, leading to less rainfall, and, combined with natural climatic variability, made the droughts of the 1970s and 80s worse than they otherwise would have been. Somewhat confusingly, the climate of the Sahel did change, but the cause was not “climate change,” the global phenomenon caused by burning fossil fuels. This is because desertification started occurring decades before there were enough greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to have caused it. Rather, the cause was massive loss of plant life. As we’ll see in Chapter 4, these two distinct problems are beginning to compound each other in dangerous ways. But the fundamental cause of desertification of the Sahel is not the burning of fossil fuels, but the loss of plant life.

Adding this all up, 75% of all water entering Lake Chad from the rivers that feed it has disappeared, from a combination of diversions for irrigation and the effects of desertification (decreased rainfall).

In sum, after more than six decades of irresponsible agricultural practices – unsustainable diversions for irrigation, overgrazing, deforestation, inadequate fallow periods – it’s not surprising that Lake Chad has nearly disappeared.

When we ended the section on diversions, two questions remained based on two inflection points. We now have the answers to those questions.

First, why did Lake Chad start losing volume in the 1960s, before major diversions started? The answer is desertification. Desertification led to a change in the climate of the Sahel – less rain was falling and thus less water was entering Lake Chad. Desertification is also the answer to the second question, centered on the second inflection point: why did diversions suddenly increase so much in the 1980s? The decrease in rainfall was also partly responsible for the diversions. Because less rain was falling, farmers made up for the shortfall in rain by diverting water from the Chari-Logone River system to grow food.

Taking a step back to see the big picture, we’ve been able to answer the questions we posed at the beginning of this section. Scientists are certain that the collapse of Lake Chad was caused by two factors: diversions from the Chari-Logone river system for agriculture and desertification. Desertification led to less rain, which in turn reduced the water flowing into Lake Chad; it also made people increasingly reliant on irrigation to water their crops since less rain was falling.

As mentioned in the beginning of this chapter, our goal here is to understand the scientific and technological aspects of the collapse of Lake Chad. The science is very clear: desertification is the underlying problem, and desertification is in turn caused by irresponsible agricultural practices, including inadequate fallow periods, overgrazing, and farming on marginal lands. Furthermore, as a technological problem, desertification has been solved: we have known how to reverse desertification for many decades, and doing so is very cheap.

In Chapter 3, we will discuss the social problems that can explain why such a severe problem with such simple solutions has been worsening for decades. However, you can probably guess why impoverished, hungry people would, for example, overgraze pasture land or plant crops on marginal farmland. The more difficult question to answer is: if desertification accounts for a quarter of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions, why does the wealthy world show so little concern?

Sign up here to be notified when a new volume of Finite is published

Diarrhea: the noisy killer

The other mystery we set out to solve in this chapter: why do so many Cameroonians lack access to drinking water?

The UN distinguishes between physical water scarcity and economic water scarcity. Physical water scarcity means there is simply not enough freshwater in an area to meet human needs. Economic water scarcity means there is enough freshwater in an area to meet human needs, but for reasons of poverty and underdevelopment, people don’t have access to enough drinking water. In fact, very few places in the world suffer from physical water scarcity; the Sahel, as with much of the thirsty world, suffers from economic water scarcity. To illustrate this insanity, 150,000 people work as fishermen on Lake Chad, a freshwater lake, harvesting 120,000 tons of fish annually. Yet none have access to clean drinking water; they rely on untreated, often contaminated groundwater and lakewater.

So – if there is enough freshwater to meet everyone’s needs, why do 51% of Cameroonians lack reliable access to drinking water?

Cameroon is blessed with so much natural wealth that it could afford to meet all of its citizens’ basic needs. Yet Cameroon is one of the poorest countries on the planet. The United Nations’ preferred way of measuring poverty is called the Multidimentional Poverty Index (MPI). It attempts to account for a multitude of different aspects of poverty beyond a person’s income. The MPI measure includes nutrition, child mortality, years of schooling, school attendance, cooking fuel, sanitation, drinking water, electricity, housing, and household assets. A score of zero means you are not deprived of any of these; a score of 1/3 means you are in multidimensional poverty, and a score of 1/2 puts you in severe multidimensional poverty. But the MPI seems like an exercise in masking the true extent of human suffering: if you have no access to drinking water, no access to sanitation, no cooking fuel, no electricity, and no housing but have access to food and schooling, you would score 5/18. Since 5/18 is less than 1/3, you would not be considered poor. Any rational person, of course, would conclude you are under extraordinary deprivation.

According to the UN, 43.6% of Cameroonians are in multidimensional poverty, with an additional 17.6% classified as “vulnerable to multidimensional poverty”. 24.6% are in severe multidimensional poverty.

There are other ways of measuring poverty, of course. Another way considers specifically income, and the results are shocking: 25.7% of Cameroonians have less than $2.15 income per day – $2.15 per day is the cutoff for “extreme poverty.” However, as with the MPI, measuring poverty in this way seems to be an exercise in masking how dire global poverty is. Americans who have traveled to less developed countries have no doubt noticed that a dollar can buy a lot more stuff than that same dollar in the US. So when people hear about $2.15 per day poverty, they think this must be somehow liveable because $2.15 in Cameroon goes so much farther than it does in the US.

Not so. The $2.15 cutoff is actually adjusted for what’s called purchasing power. When this type of poverty is measured, researchers adjust for the fact that $2.15 goes farther in, say, Cameroon than in the US. In other words, it’s not really $2.15 per day; it’s less than that. Surviving in Cameroon on $2.15 after adjusting for purchasing power is like trying to survive in the US on $2.15 per day.

Again, this way of measuring poverty seems like an exercise in deceiving the public on how dire global poverty is: it is natural to assume that $2.15 (or $64.50 per month) represents some kind of liveable wage in Cameroon because $2.15 goes so much father in Cameroon than in the US. Too few people look more closely at the methodology and discover that – because of purchasing power adjustments – “extreme poverty” in countries like Cameroon is like trying to survive on $64.50 per month in the US.

Another way to look at poverty in Cameroon is to look at hunger. According to USAID, 2.6 million Cameroonians (or 9.6% of the population) are in phase 3 or worse levels of food insecurity. Phase 3 is the “crisis” phase. Phase 1 is “minimal” food insecurity, while phase 5 is a full-blown famine.

Since our focus in Issue 1 is drinking water, let’s look more closely at the issue of drinking water in Cameroon. According to WASH data from the World Health Organization and UNICEF, 21% of Cameroonians never have access to clean drinking water: 15% drink water untreated from wells or springs that may be contaminated, and 6% drink straight from surface water like rivers, despite notorious pollution. Only 35% of Cameroonians have access to drinking water in their home, and only 49% have access “when they need it”, though not all of this drinking water is free from contamination. As we saw in the introduction for Issue 1, these statistics make Cameroon a case study and not an outlier. Throughout the Sahel and around the world, billions of people go thirsty, and Cameroon is unfortunately not unique.

Statistics on the other everyday use for water – sanitation – are not much better. According to the UN, a shocking 35% of Cameroonians have no access to improved sanitation – WASH classifies unimproved sanitation as toilets that flush to an open drain, open pits, and the like. An additional 6% are practicing open defecation, i.e., they don’t even have a hole in the ground to relieve themselves and have to use a ditch or a bush. 60% of Cameroonians have access to what the UN terms “improved sanitation,” but of these, a quarter have limited access because they share with other households.

For those lucky 60% of Cameroonians with at least some access to improved sanitation, it’s worth noting that some very rudimentary setups are included in the UN’s definition of “improved sanitation.” Just 1% of all Cameroonians have a sewer connection and only 13% have access to a septic tank. In other words, just 14% of Cameroonians have what we in the US would consider adequate sanitation. The remaining Cameroonians with “improved sanitation” mostly use a pit latrine with a concrete slab. This consists of a hole covered by a concrete slab (with a hole that people squat over) and a shelter over the concrete slab. A latrine without a concrete slab would meet the UN definition of unimproved sanitation, and for good reason. Though rudimentary – the smell inside a concrete slab pit latrine ranges from unpleasant to overpowering – there are substantial benefits to even this rudimentary setup.

Cholera, for example, spreads when a fly lands on the feces of someone infected with cholera, and then that same fly lands on someone else’s food, thus leaving the cholera bacteria on the food. Transmitting pathogens in this way is a massive risk for an open latrine, but substantially reduced with a concrete slab latrine: to spread diseases like cholera, a fly would have to buzz its way into the shelter housing the latrine, then find its way into the small hole in the concrete slab, then land on the human waste, then find its way out the small hole in the concrete slab, then find its way out the latrine’s shelter. Even rudimentary improvements to latrines dramatically reduce the risk of disease transmission.

In any case, adding this up, of the 60% of Cameroonians with improved sanitation, 1% have a sewer connection, 13% have a septic tank, and 46% are using latrines. In other words, even the topline finding from WASH, that 60% of Cameroonians have access to improved sanitation, loses its luster when we see that most of those people use a very rudimentary concrete slab latrine.

Finally, WASH does not classify a concrete slab pit latrine safely managed unless the human waste is eventually treated. Once filled, the waste in the latrine needs to be treated and then covered or pumped out and taken offsite to be treated. If this is not done, there is the potential for water pollution and the spread of waterborne illness. The UN does not have adequate data to estimate the number of Cameroonians who have safely managed sanitation.

Safely managed sanitation matters because inadequate sanitation has catastrophic consequences. While cautioning that their data underestimate the extent of the problem, the World Health Organization estimates that 2.5% of all deaths worldwide (1.4 million) in 2019 were caused by inadequate sanitation (far exceeding deaths from armed conflict) and that inadequate sanitation killed more than 22,000 Cameroonians in 2019. Of course, all of this is preventable; as a technological problem, sanitation has been solved for centuries.

In sum, only 49% of Cameroonians have access to drinking water “when they need it,” and even that water is not always free from contamination. 21% of Cameroonians never have access to clean drinking water, and only 14% have what we in the US would consider adequate sanitation – a sewer connection or septic tank. As with drinking water, Cameroon’s challenges with sanitation are not unique among countries of the Sahel. Compared to 14% in Cameroon, just 30% of people have access to a sewage line or septic tank in Nigeria; 25% in Gambia; 8% in Mauritania and Eritrea; 7% in Sudan; 6% in Niger; 5% in Mali; 3% in Burkina Faso; and in Chad, the Central African Republic, and South Sudan, less than 2%.

Nonetheless, Cameroon has been moving in the right direction, albeit far too slowly. For example, from 2015 to 2020, the percentage of Cameroonians who had access to clean water “when they need it” increased from 47% to 49%. Ironically, as climate change has been accelerating, access to drinking water – in Cameroon and the entire world generally – has been improving. As mentioned in the introduction, a quarter to half of people worldwide lack access to drinking water. Clearly, climate change is not the biggest threat to people’s access to drinking water now or for the foreseeable future; human folly is. To be clear, this doesn’t mean that climate change isn’t a problem, or that climate change won’t make these problems harder to solve. But clearly, stopping climate change isn’t going to get Cameroonians drinking water.

One man’s jihad is another man’s failed millet crop

Another way to understand the desperation in Cameroon and around Lake Chad is to see how many people have turned to violence. Desperate people turn to violence when they have no other options. Cameroon and the other Lake Chad countries are fighting a protracted war against several militant groups centered around Lake Chad, including Boko Haram, which engages in grisly, indiscriminate violence. In a single attack in 2019 near the Cameroon-Chad border, Boko Haram killed 50 fishermen going about their day.

Though the rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria is beyond the scope of what we can cover here, its expansion into Cameroon and the motivations for Cameroonians to join are instructive. A lengthy investigation by the Washington Post found much support for the “finding by the United Nations this year that the opportunity for jobs, rather than religious ideology, is the main reason that people join extremist groups across Africa.” Post reporters interviewed many former Boko Haram fighters who said that most of their former comrades joined out of desperation rather than any sort of religious devotion. One fighter said that he joined Boko Haram when his family’s millet crop failed, leaving them destitute. “They said it is about religion, but it is nothing close to religion,” the man told reporters. Another local told reporters that his brother joined when losing his cattle left him in penury. “Mbodou said he begged his brother not to go. But his brother insisted. ‘I have to feed my family,’ Mbodou recalled his brother saying as he left.”

Reporters also spoke to American, French, and Cameroonian military officials, as well as locals affected by the violence – all agreed that extreme poverty, hunger, and hopelessness – not religion or ideology – explain the rise of militant groups like Boko Haram.

Image: Nigerien soldier on patrol against Boko Haram insurgency

In addition to the dangers of militants, lack of drinking water is turning nominally safe areas into powder kegs. Says one Lake Chad official, “if you have a community that has only one or two boreholes that provide drinking water, how do thousands of refugees get water? This causes strain and, in turn, more conflict risk with host communities.”

Besides joining a militant group, the other options are suicide, which the African Development Bank estimates thousands have chosen following crop failures, or braving the extremely dangerous trip to Europe in search of a better life.

Meanwhile, on the opposite end of Cameroon, militants in the English-speaking part of the mostly French-speaking country have launched a civil war. Thousands of people have been killed, over 700,000 have been displaced, and 1.3 million are in need of humanitarian aid. Though nominally a separatist movement, anthropologist Rogers Orock and others have argued that the revolution should not be understood as a separatist movement as much as “resentment of the authoritarian rule” of Paul Biya.

This introduces our first villain: Paul Biya.

Paul Biya

Image: Paul Biya in 2014

At age 91, Paul Biya is the world’s oldest head of state. Biya has served as Cameroon’s president for a shocking 42 years. Cameroon has an embarrassment of natural riches. How can a country with so much natural wealth be so poor? International relations scholar David Kiwuwa explains:

Cameroon is a leading exporter of timber in Africa and [the] fifth largest cocoa producer in the world. [ ] The country should have enough resources to reduce extreme poverty and underdevelopment. Yet the proceeds are plundered through corruption and to maintain a clientelist network…Nothing substantive gets done without the sign-off of the president. No arm of government or entity of the state has gone unpoliced, including the judiciary: judges are nominated directly by the president.

Simply put, there is no facet of public life untouched by the Biya regime.

Journalist Vava Tampa echoes this but is less judicious in her word choices (emphasis added):

Biya has misruled with an iron fist for nearly 40 years…As Africa’s largest producer of timber and the world’s fifth-largest producer of the cocoa, Cameroon should be a rich country. But Biya’s life-presidency, corruption and use of indiscriminate violence as a first resort have made Cameroon a country in crisis[.] For me, the best way forward…is to force out Biya, whose tentacles pry into every aspect of the country, choking life and talent. [Biya and Cameroon’s elites] kill with impunity.

Biya is undefeated in presidential elections, winning an astonishing eight presidential elections. In 2024, Biya stated he would run for reelection to his ninth term in 2025 – when he will be 92(!).

So, how does Biya win so many elections despite being an obvious kleptocrat? He steals them.

Biya has shown remarkable ingenuity to maintain his grip on power. At first, he outright banned opposition parties and ran in elections unopposed. Later, once he figured he was sufficiently capable of rigging elections, he allowed opposition parties to run – but stuffed the ballot boxes. In recent decades, Biya has become more resourceful – even, ingenious – in his efforts to maintain his grip on Cameroon. Kiwuwa (the international studies scholar) explains (emphasis added) that Cameroon has more than 300 political parties,

many allegedly secretly bankrolled and controlled by Biya. They provide a façade of democratic competitiveness. In reality, they have weakened legitimate political opposition. [] The absence of a united and consolidated opposition has enabled the entrenchment of a dominant party system. The ruling party has a dominant majority in both the National Assembly and the Senate (63 seats of 70). This erodes any chance of genuine checks and balance…Elections have become little more than a procedural inconvenience, where Biya runs with no possibility of losing.

Cameroon has the ignoble distinction of being judged the most corrupt country on earth for two consecutive years. This corruption enables Biya to steal from all corners of Cameroon, enriching himself and the villains who help him.

Unfortunately – as we’ll see in Chapter 3 – neither Paul Biya, his greed, nor his tactics, are unique. While Cameroon and Biya are very useful as a case study, dictators from the Philippines to Central America have equaled or exceeded Biya’s ignoble accomplishments.

Biya is uninterested in addressing the root causes of Cameroon’s problems – not the root causes driving recruitment to Boko Haram and related insurgencies around Lake Chad, nor the English-speaking separatists. Orock, the anthropologist, argues that Biya refuses to negotiate with the English-speaking insurgency for fear of looking weak – even though his violent command of the war has backfired and further galvanized support for the militants.

With this in mind, it’s not hard to see why so many Cameroonians lack access to clean drinking water. All aspects of the government are controlled by Paul Biya, and all are devoted to enriching him. After more than four decades of rule, Biya has shown no interest in building out the infrastructure to ensure all Cameroonians have access to clean drinking water.

Biya also contributes directly to desertification. We noted above that one of the major causes of desertification in the Sahel is deforestation. In 2019, 3.3 million cubic meters of timber were felled in Cameroon, and $934 million worth of Cameroonian timber was exported in 2018. Though it’s not possible to know how much Biya steals from the timber trade, he profits from everything in Cameroon and the lucrative timber trade is no exception. By cashing in on the timber trade, Biya thus profits directly from desertification. Biya will not halt Cameroon’s unsustainable deforestation because he profits directly from it; after all, he is 91 and will not live to see the consequences of these actions.

Debt

There is one more major villain lurking in the wings. Each year, Cameroon pays between a fifth and a quarter of all government revenue towards servicing debt. Cameroon’s debts are so large that even with these massive payments, they will never be able to pay them all off. Chapter 3 explores the outrageous circumstances that created high levels of debt in Cameroon and in poor countries around the world.

So even if Paul Biya could somehow be replaced by a government responsive to the will of the people, their ability to build out expensive drinking water infrastructure projects would be limited by the debt Cameroon owes.

Conclusion

We now know why Lake Chad collapsed: desertification and unsustainable diversions for agriculture. Desertification was caused by decades of irresponsible agricultural practices. The science behind desertification – including how to reverse it – has been understood for many decades.

So, we have a problem for which we have understood the underlying causes for decades, and we have understood the solutions for just as long, and the solutions are relatively cheap. In other words, this is not a technical or economic problem; the technical problems have been worked out decades ago, and the solution is not expensive to implement. So what’s the problem? If desertification is so cheap and easy to fix, why hasn’t it been? And if desertification is responsible for a quarter of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions, why does the wealthy world show so little concern for the Sahel?

Similarly, we know why the government of Cameroon won’t build out infrastructure to ensure access to clean drinking water for ordinary Cameroonians: they are ruled by a corrupt dictator indifferent to the extraordinary suffering of those around him. And Cameroon’s massive debts mean that even a government responsive to the will of its people would be limited in what it could do to build out infrastructure. In sum, it’s not hard to see why a grossly indebted country ruled by a kleptocratic dictator wouldn’t have basic drinking water and sanitation infrastructure. But this leaves us with even more questions. Why is Cameroon ruled by a kleptocratic dictator? Why is Cameroon so indebted?

We’ll unravel these mysteries in the next two chapters.

A

A

When discussing global poverty, it can be hard to keep perspective. These these are real people in real places. To help us keep a healthy perspective, we’re ending with a focus on Cameroonian culture.

Did you know that Cameroon has the most successful men’s soccer team in Africa? The Indomitable Lions have been to the World Cup more times than any other African team. In fact, Cameroon is the only team to have ever beaten Brazil. Here are highlights from the second time Cameroon beat Brazil, in the 2022 World Cup:

From Douala on the Gulf of Guinea, to Maroua at its northernmost tip, points between and beyond, rise and celebrate!!!