Your cart is currently empty!

@#$% You, Freshwater!

Introduction to Issue 1

Issue 1 of Finite explores two catastrophes, both related to freshwater: the collapse of Lake Chad and inadequate access to drinking water in Cameroon, one of the four countries that borders Lake Chad.

Before its collapse, Lake Chad was larger by surface area than two North American Great Lakes, Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. By surface area, Lake Chad was once the eleventh largest lake in the world. According to the United Nations, “[T]he lake’s size has decreased by 90 per cent [and] the surface area of the lake has plummeted from 26,000 square kilometers in 1963 to less than 1,500 square kilometers today. In the 1960s, the lake hosted about 135 species of fish and fishermen captured 200,000 metric tonnes of fish every year, providing an important source of food security and income to the basin’s populace and beyond.” It was full of inhabited islands, each with its own culture. According to BirdLife International, Lake Chad is one of the most important places in the world for migratory birds, as over 70 species rely on Lake Chad as a stop in their migration.

____________________________________

Issue 1: Climate Change and Freshwater

Intro: Why did Lake Chad collapse and why are Cameroonians so thirsty?

Chapter 1: Desertification of the Sahel and Cameroon’s water infrastructure

Chapter 2: Cameroon gains “independence” from France

Chapter 3: Poverty, structural adjustments, and dictators

Chapter 4: The US New Deal’s Soil Conservation Service is a proven model

Bonus 1: More on Cameroon’s independence movement

Bonus 2: How did Ahidjo make himself a dictator?

Bonus 3: How did Biya take control from Ahidjo?

_____

Issue 1 is available in written and podcast format

__________

Fishing has historically been a significant source of employment in the area. In the past, fishermen lived on Lake Chad’s banks, fishing all day, then returning to town to sell their fish right off the boat. Now, the lake has receded so far that many fishermen can no longer access it. Some fishermen travel more than 20 kilometers to get to the shore and then that same distance back with the day’s catch to sell it. As one of the poorest places in the world, this feat must be accomplished often without an automobile and with a very perishable product. Aside from the loss of livelihoods, the lake’s shrinking also means a loss of fish, precipitating greater hunger and loss of a nutritious source of protein in one of the world’s poorest regions.

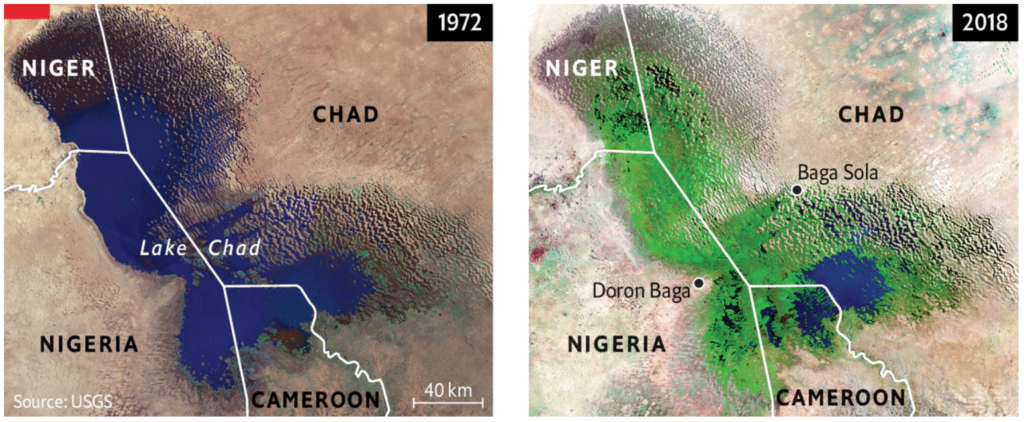

Before its collapse, Lake Chad covered approximately the same area as the states of Vermont or Maryland. Now, it is comparable in size to any of Maryland’s 23 counties or the city of Los Angeles. Satellite photos showing the extent of the catastrophe are stunning:

Meanwhile, the UN estimates that only 49% of Cameroonians have access to drinking water when they need it and only 35% have access in their homes; yet even that drinking water is often contaminated. Blood is already being spilled in Cameroon over water scarcity: “Cameroonian officials say hundreds of people have fled its northern border with Chad after an ongoing conflict over water between cattle ranchers and fishermen killed 18 people and wounded 70.”

So, a massive freshwater lake collapses, losing 90% of its volume. And in one of the countries bordering Lake Chad – Cameroon – just under half the population has reliable access to drinking water. It certainly seems like these problems are related. If a major body of freshwater has nearly disappeared, then certainly the people nearby could run out of water to drink. And climate change could be the cause of it all.

Yet climate change can’t be responsible. Lake Chad started collapsing in the 1960s, decades before there was enough greenhouse gas in the atmosphere to have caused it. And the number of Cameroonians in a given year lacking access to drinking water bears no relationship to Lake Chad’s volume.

Violence, collapsing ecosystems, lack of drinking water – in Cameroon and Lake Chad, all of our worst fears of climate change are already happening, but climate change is not responsible. What is going on?

What if we’re thinking about climate change all wrong? What if climate change isn’t the biggest threat to the planet, but rather a single – albeit large and important – symptom of a more fundamental problem?

The other source of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions

Though climate change is not responsible for the collapse of Lake Chad, these crises are nonetheless related. In fact, the opposite is closer to the truth: the crisis driving Lake Chad is also a major contributor to climate change.

As we will learn in Chapter 1, land degradation is the fundamental cause of the collapse of Lake Chad. Land degradation is also a massive crisis throughout the entire Sahel – that’s the large strip of Africa running east-west from the Atlantic Ocean to the Indian Ocean, sandwiched between the Sahara Desert to the north and Africa’s tropical rainforests to the south – not just in Cameroon and not just among the Lake Chad countries.

According to the latest data, a quarter of all of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions come from land degradation. Earth’s soils are estimated to hold 2,500 billion tons of carbon, or more than three times as much carbon as is held in the atmosphere. When land is degraded, the carbon that had been contained in the soil is released into the atmosphere where it acts as a greenhouse gas. In this way, land degradation is no different than a coal power plant: once in the atmosphere, carbon acts as a greenhouse gas no matter its origin. In other words, the basic cause of the collapse of Lake Chad is also contributing in a massive way to climate change.

Thus, even though we may not want to care about some lake half a world away, we must. We all share one atmosphere, and unless we get a handle on the hotspots of land degradation – the Sahel, Mongolia, and parts of Central and South America – we won’t be able to stop climate change. Unless we can stop land degradation the world over, we will never reach zero emissions. A complete elimination of fossil fuels will not deal with the world’s land degradation crises and therefore will not stop a quarter of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions.

We cannot stop climate change without understanding and solving the collapse of Lake Chad.

As goes Cameroon and Lake Chad…

Cameroon and Lake Chad are valuable case studies to understand issues with freshwater around the world. Cameroon’s challenges with drinking water are – unfortunately – not unique. Some of the other countries of the Sahel have comparable or even worse access to drinking water: In Burkina Faso, only 56% of people have access to clean water when they need it; in Senegal, 53%; in Chad, 48% ; in the Central African Republic, 38%; and in Niger, 33%. Nor is this a problem unique to the Sahel; according to the latest data from the World Health Organization (WHO), 26% of humanity does not have access to clean drinking water. Ironically, as climate change has been accelerating, the number of people without access to clean drinking water has actually been decreasing, albeit at too slow a pace. However, a more recent study in Nature argues that the WHO has underestimated the problem and that 4.4 billion people – a majority of humanity – lack access to clean drinking water. Whatever the dataset, billions are without clean drinking water.

While Cameroon’s issues with drinking water are not unique, Cameroon is an especially useful case study because the villains are so clear. Astonishingly, since it became independent from France in 1960, there have only been two presidents: Ahmaduo Ahidjo, whom the French appointed before independence, and his hand-picked successor, Paul Biya. This unbroken chain of rule from colonial times to today means Cameroon’s villains cannot use the vagaries of history to hide what they have done. Understanding Cameroon thus allows us to more easily understand challenges with drinking water in countries where the political leadership has had a wider cast of characters.

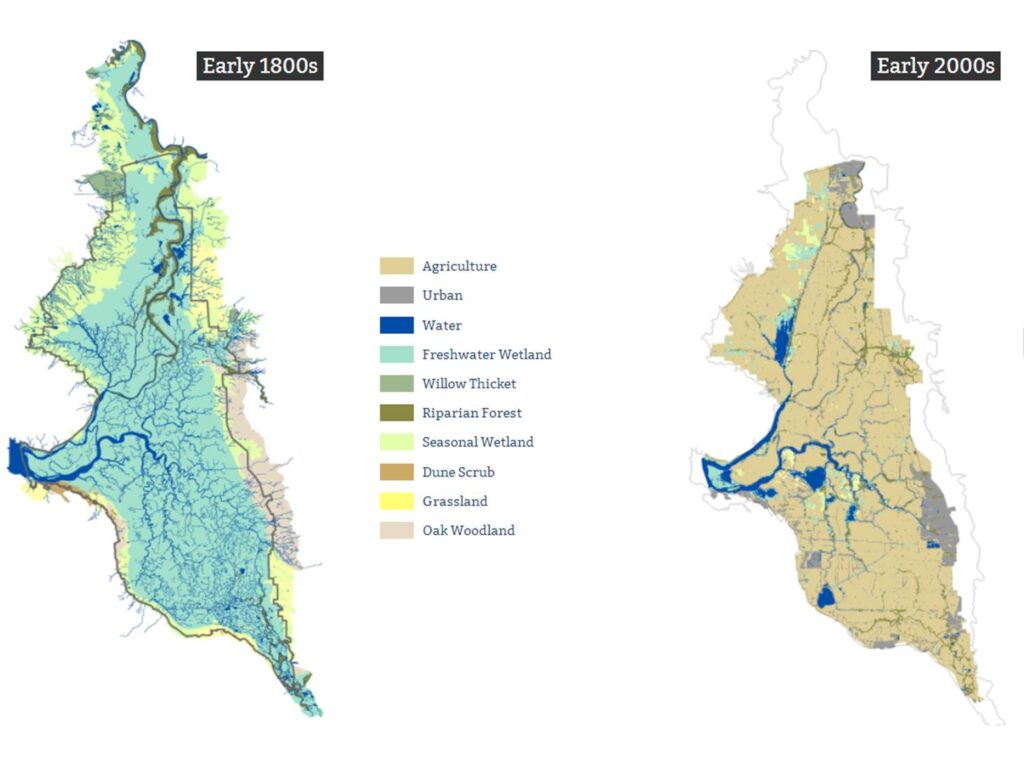

Similarly, Lake Chad is not the only freshwater ecosystem in the world to collapse. The Aral Sea, once the third largest lake in the world, has lost 90% of its volume. 90% of the Mesopotamian Marshes wetlands have been wiped out. The volume of Russia’s Lake Chany has been cut in half. California’s Tulare Lake – once the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi – has been reduced from 690 square miles to 2 square miles. The Colorado River – the source of water for 40 million people – has been badly overdrawn for a century and could literally run dry in places. In parts of the United States, so much groundwater has been unsustainably withdrawn over the past two centuries that the water table – the depth at which groundwater can be accessed – has fallen a shocking 900 feet in some places. As a result, parts of the US have been sinking for decades: parts of central California have lost 28 feet of elevation due to grossly unsustainable withdrawal of groundwater. The vast freshwater wetlands of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, once a stop-off for tens of millions of migrating birds, have been almost totally wiped out:

Like the Lake Chad catastrophe, none of these crises have been caused by climate change. Rather, human mismanagement is the culprit. If we understand the basis of the Lake Chad catastrophe, we can understand these other crises as well.

There is enough fresh water

For the foreseeable future, more people worldwide will continue to go thirsty due to human folly than the effects of climate change. More ecosystem collapse will be caused by human folly than climate change. Though climate change will surely make these problems worse, it won’t have caused them: collapsing freshwater ecosystems and billions going thirsty is simply how the world works. Our greatest fears of climate change are already happening.

Yet none of this is necessary. There is enough freshwater to support all humanity without sacrificing natural gems like Lake Chad – that is, if we responsibly manage these precious resources.

As we’ll learn in Chapter 3, the single largest contributor to these many problems is poverty. And as we’ll learn in Chapter 4, some of the villains perpetuating poverty in the Sahel are directly controlled by the governments of developed countries, especially the United States. These are not merely problems you can contribute to as a citizen of a wealthy country, but rather villains that cannot be stopped without people like you.

Since poverty is the root cause of so many environmental problems, there is no such thing as environmentalism without meeting everyone’s basic needs. There is no reversing the collapse of Lake Chad nor the land degradation in the Sahel without addressing poverty. And since we must reverse land degradation in order to reach zero emissions – remember, a quarter of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions comes from land degradation – we cannot stop climate change without meeting everyone’s basic needs. We might not want to care about a lake we will never visit or people we will never meet, but we all share one atmosphere, and unless we can solve the Sahel’s land degradation crisis, we cannot prevent catastrophic climate change.